Abstract

Excerpted From: Noura Erakat, Darryl Li and John Reynolds, Race, Palestine, and International Law, 117 AJIL Unbound 77 (2023) (24 Footnotes) (Full Document)

While the prohibition of apartheid was being developed as an anti-racist instrument in international law, a parallel effort was underway with respect to naming Zionism as a specific form of racism. In the UN's “Decade Against Racism” initiative, a coalition of states sought to insert the word “Zionism” into texts wherever colonialism, racial discrimination, alien subjugation, and apartheid appeared. On November 10, 1975, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 3379, recognizing Zionism as a form of racism. The resolution explicitly named Zionism alongside “colonialism and neo-colonialism,” as well as apartheid, and also cited an Organization of African Unity resolution naming the “common imperialist origin” of the “racist regime[s]” in Palestine, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

While the prohibition of apartheid was being developed as an anti-racist instrument in international law, a parallel effort was underway with respect to naming Zionism as a specific form of racism. In the UN's “Decade Against Racism” initiative, a coalition of states sought to insert the word “Zionism” into texts wherever colonialism, racial discrimination, alien subjugation, and apartheid appeared. On November 10, 1975, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 3379, recognizing Zionism as a form of racism. The resolution explicitly named Zionism alongside “colonialism and neo-colonialism,” as well as apartheid, and also cited an Organization of African Unity resolution naming the “common imperialist origin” of the “racist regime[s]” in Palestine, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

Resolution 3379 was informed by analyses of Zionism's racist and colonial character previously developed within the Palestinian liberation struggle. The resolution's primary architect was none other than Fayez Sayegh. Sayegh highlighted how racial purity, segregation, and supremacy constituted Zionism. At the United Nations, Sayegh explained that for Zionism, “it was the racial link that made a Jew a Jew,” and proceeded to demonstrate this point by reading aloud writings by the founder of modern Zionism, Theodor Herzl. Proponents of this argument understood the irony inherent to Zionist claims of a singular Jewish race reflecting a pillar of antisemitism that rendered Jews ineligible for inclusion within Europe.

The best-known objection to Resolution 3379 unsurprisingly came from the United States. U.S. ambassador Daniel Moynihan rejected the idea that Zionism could be a form of racism, and insisted on understanding Zionism as a political movement--a point critics like Sayegh would not dispute, but one that Zionists themselves routinely elide in their insistence that any criticism of it is tantamount to an attack on Jews as such. Ostentatiously quoting dictionary definitions of racism that invoked biological notions of race, Moynihan insisted that Jews are not a race in the biological sense. This was, of course, a complete non sequitur. As Sayegh and others had convincingly demonstrated, what mattered was not whether Jews are a race in any “objective” sense, but rather how Zionism itself understands Jews. Moynihan's fixation on biological notions of race was unsurprising, given his notoriety in debates over racism and anti-Blackness within the United States. A decade before his strenuous defense of Zionism at the United Nations, Moynihan was the lead author of a widely cited U.S. government report on “the Negro family,” whose pathologization of Black mothers fueled decades of Black feminist critique.

Resolution 3379 was passed thanks to overwhelming support from Third World states, but the voting was contentious: seventy-two states in favor; thirty-five against; and thirty-two abstentions. In Israel, the United States, and other bastions of Zionism, Resolution 3379 became a symbol of a United Nations taken over by insurgent Third Worldist, anti-Israel sentiments. Largely overlooked in the legacy of these debates was how the condemnation of Zionism as racism explicitly understood racism as part and parcel of a colonial regime.

But 1975 was in some ways a high-water mark of Third Worldist--and, by extension, Palestinian--influence in the United Nations. In the following years, the Palestinian liberation movement did not advance a legal strategy to address Zionism in international law as a jus cogens violation or a crime against humanity, as had been done with apartheid. By 1991, the Palestine Liberation Organization agreed to rescind the resolution as a precondition for entering the Oslo Peace Process. Thereafter, the U.S.-led bilateral negotiations have obscured the racial and colonial dimensions of the Palestinian freedom struggle and framed it as a matter of conflict resolution, despite the stark maldistribution of power between a nuclear power and a stateless people.

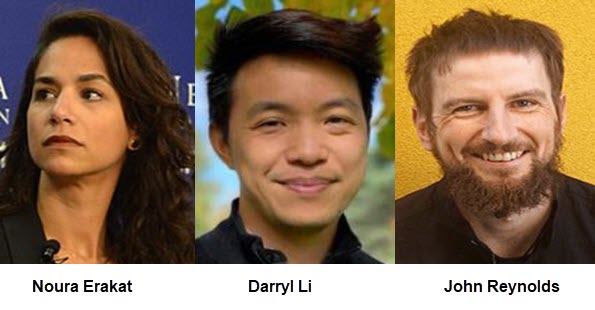

Noura Erakat, Associate Professor, Department of Africana Studies and Program in Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, United States.

Darryl Li, Assistant Professor, Anthropology, and Associate Member, Law School, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States.

John Reynolds, Associate Professor, School of Law & Criminology, Maynooth University, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Ireland.