Abstract

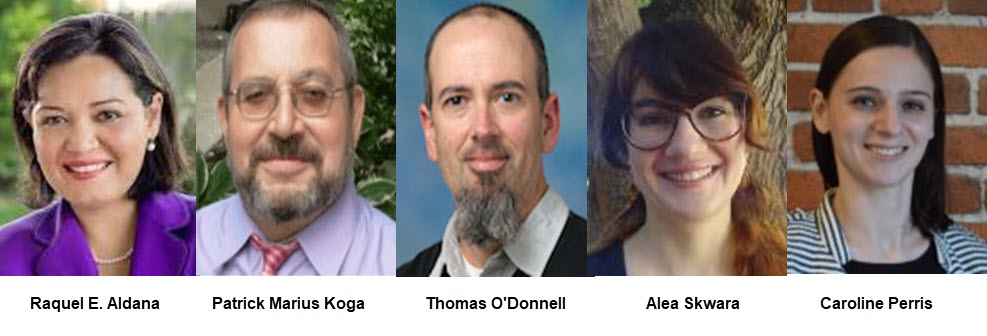

Excerpted From: Raquel E. Aldana, Patrick Marius Koga, Thomas O'Donnell, Alea Skwara and Caroline Perris, Trauma as Inclusion, 89 Tennessee Law Review 767 (Summer, 2022) (197 Footnotes) (Full Document)

For much of U.S. history, policymakers have sought to maximize sovereign power to decide when to open or shut the nation's borders to foreign nationals. The U.S. has consented to open borders for foreign nationals it deems desirable while simultaneously retaining nearly absolute power to rescind, consent, or deny entry altogether to those perceived as undesirable. While not unique, U.S. immigration laws' measurement of desirability has been ripe with bias and nationalistic notions of what is best for “America.” A great deal has been written about a range of these biases--e.g., racism, classism, ableism that also have documented unfinished projects of undoing bias--and the tendency to repeat our history. The U.S. search for desirable immigrants involves a weeding out process that objectifies and dehumanizes migrants deemed undesirable. To be desirable, migrants must perform a utility furthering U.S. interests, which also means they cannot be “broken.” Under these criteria, the poor, the disabled, those with a criminal history, those with mental illnesses, or those who have endured trauma are often rejected. The dehumanization of the undesirable foreigner occurs since adjudicating who is desirable and who is not can be brutal, and yes, traumatizing or re-traumatizing.

For much of U.S. history, policymakers have sought to maximize sovereign power to decide when to open or shut the nation's borders to foreign nationals. The U.S. has consented to open borders for foreign nationals it deems desirable while simultaneously retaining nearly absolute power to rescind, consent, or deny entry altogether to those perceived as undesirable. While not unique, U.S. immigration laws' measurement of desirability has been ripe with bias and nationalistic notions of what is best for “America.” A great deal has been written about a range of these biases--e.g., racism, classism, ableism that also have documented unfinished projects of undoing bias--and the tendency to repeat our history. The U.S. search for desirable immigrants involves a weeding out process that objectifies and dehumanizes migrants deemed undesirable. To be desirable, migrants must perform a utility furthering U.S. interests, which also means they cannot be “broken.” Under these criteria, the poor, the disabled, those with a criminal history, those with mental illnesses, or those who have endured trauma are often rejected. The dehumanization of the undesirable foreigner occurs since adjudicating who is desirable and who is not can be brutal, and yes, traumatizing or re-traumatizing.

This article tells this story of objectification and dehumanization centered around migrant trauma. Our purpose is to make migrant trauma more visible and to contrast immigration law's conception and adjudication of trauma to how the term and its treatment has evolved in other fields, including psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience, and anthropology. Migrant trauma encompasses several types of experiences. It includes experiences of physical or psychological harm, whether in the past or in the future, that become the basis for an immigration remedy--either as a ground for inclusion or a repair against removal. This type of trauma is not directly related to U.S. immigration law and practices but can be the push factor for forced displacement (e.g., persecution or natural disaster) or arise from vulnerabilities of immigrants in irregular status who experience victimization (e.g., crime or human trafficking). Migrant trauma also includes harm that is directly caused by the enforcement of borders. This can include when migrants are separated from family and communities to whom they have deep ties through exclusion or removal. It also includes the adjudication of borders, such as legal processes or detention practices that re-traumatize or create new trauma when migrants attempt to seek relief from exclusion or removal.

The good news is that the treatment of certain types of trauma in immigration law increasingly operates as a force of inclusion rather than exclusion. This has occurred both through jurisprudential developments that have imposed some constitutional limits on the immigration power through the recognition of the humanity of certain migrants and the brutality of the immigration power. In tandem, Congress and the Executive have also, at times, created immigration paths based on trauma or have sought to ameliorate, in some cases, the brunt and the enforcement of borders. The challenge that remains is that these developments in immigration law remain narrow, arbitrary, and uninformed by the science of trauma. In fact, how trauma is conceived and adjudicated in the immigration system-even when oriented toward inclusion-remains deeply flawed in ways that threaten to undermine the entire project of embedding borders and their enforcement with greater humanity.

This article proceeds in four parts. Part I explains how trauma is understood in a Western psychological model and across other cultures. This section serves to contextualize the dominant mode of understanding trauma in the United States, as well as to highlight the shortcomings of medicalized definitions of trauma both generally and in the specific case of refugees and asylum seekers. This article then chronicles two aspects of the role of trauma in immigration law. Part II documents the involvement of health authorities in federal immigration proceedings from the late nineteenth century through the Second World War that facilitated the exclusion of persons based on their mental “fitness”. This exclusion was also informed by eugenics and the racism prevalent at the time. After the Second World War, some developments in mental health, progress in racial justice, the horrors of the Holocaust, and Cold War political considerations contributed to lessen, but certainly not eliminate, the biases against immigrants with histories of trauma. This period of dim enlightenment coincided with parallel humanizing trends in immigration law, documented in Part III, that began to treat trauma as a force of inclusion in immigration law. Part III A, which we label “Immigration Law's Humanitarianism,” documents the beginnings of immigration law's embrace of grave instances of migrant physical and psychological trauma, whether arising from state persecution or other types of violent crimes waged by private actors, as grounds for inclusion. This turn also included limited instances of state or collective trauma to offer temporary protection to certain nations enduring grave man-made or natural disasters. Part III B turns to executive and legislative adoption of discretionary remedies against removal, recognizing immigrants' stakes to family, community, or belonging as members of U.S. society. Finally, Part IV assesses immigration law's current approach to documenting trauma. We discuss the significant gaps between this approach and current psychological and neuroscientific understanding of the impact of trauma, and the barriers to inclusion it presents. We suggest initial steps for reform that incorporate the science of trauma, and the principles of compassion and fairness.

[. . .]

As we develop more inclusive approaches to adjudicating trauma, we must be vigilant to ensure that we do not inadvertently create more avenues for bias and exclusion. In addition to wider adoption of established interational standards for the documentation of trauma, we suggest several efforts that we can collectively engage in to work toward meaningful inclusion. The first is to approach mental health forensic assessments as an educational, rather than diagnostic, tool. That is, instead of attempting to fit an asylum seeker or victim of crime into a Western medical diagnosis to prove the validity of their claim, these assessments should be used to elucidate what, for this individual, credibility might look like. To do this effectively requires culturally-appropriate and trauma-informed assessors and clinical assessment tools. Currently, access to these resources is extremely limited. Second, we must address barriers to access, including access to legal representation, the availability of appropriately trained assessors, and the financial burden to petitioners. Third, we must continue to seek the reform areas of immigration law and practices with wide gaps in scientific understanding on the impact of trauma, or at a minimum train immigration advocates and adjudicators in science-informed understandings of trauma in the application of current standards. This will help build realistic expectations for credibility and support their ability to more fairly and accurately represent and adjudicate cases that involve trauma. The fourth is to push for creating a more trauma-informed process on the whole. This includes adopting alternatives to immigration detention and developing more trauma-informed interview processes and court proceedings, both to avoid perpetuating trauma and to provide fair and equitable grounds for petitioners to make their case. Other areas of law have already begun similar processes under the theoretical framework of therapeutic jurisprudence, in the context of mental health criminal courts or in the handling of child abuse cases. The application of therapeutic jurisprudence to the immigration system generally is a much larger question we hope to take up in a future article. Others have started to make very useful and excellent contributions to considering its possible uses and contributions in other aspects of immigration law and practice. Finally, we must engage in cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural dialogue. This will help us bridge the legal-scientific gap and identify leverage points where the conversation between the law and science can be generative. Through all this work, we must maintain humility and a humanitarian orientation and learn from the history of how scientific perspectives have been used to justify and perpetuate harm. We recognize that these initial suggestions are far from exhaustive and, at the same time, daunting. The greater project of working toward meaningful inclusion is a long one. We hope our collective work offers a piece of the roadmap to how we can create an immigration system that more clearly reflects the principles of compassion and fairness.

Martin Luther King Jr., Professor of Law, UC Davis School of Law, King Hall.

Associate Professor and Director of Ulysses Refugee Health Research Program, UC Davis School of Medicine, Dept. of Public Health Sciences, Divisions of Epidemiology and Health Informatics.

Analyst, Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, UC Davis.

Postdoctoral Scholar, Center for Mind and Brain and Global Migration Center, UC Davis

J.D. candidate, University of California, Davis, School of Law, Class of 2022.