Become a Patreon!

Abstract

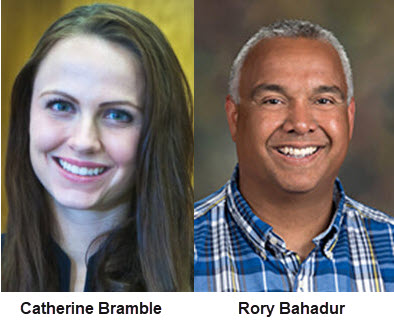

Excerpted From: Catherine Bramble and Rory Bahadur, Actively Achieving Greater Racial Equity in Law School Classrooms, 70 Cleveland State Law Review 709 (2022) (303 Footnotes) (Full Document)

2020 was a year no one will soon forget. On March 11th, the World Health Organization classified COVID-19 as a global pandemic, and it became the most serious pandemic in over one hundred years. Countries issued nationwide lockdowns, healthcare systems became overwhelmed, and unemployment rates soared.

2020 was a year no one will soon forget. On March 11th, the World Health Organization classified COVID-19 as a global pandemic, and it became the most serious pandemic in over one hundred years. Countries issued nationwide lockdowns, healthcare systems became overwhelmed, and unemployment rates soared.

On May 25, 2020, a 46-year-old black man named George Floyd was arrested by police in Minneapolis and died in police custody after a white officer knelt on his neck until paramedics arrived at the scene. Three days later, a 911-call from Kenneth Walker was released to media outlets--a call he made after his girlfriend, a black woman named Breonna Taylor, was fatally shot on March 13, 2020 by police officers using a no-knock warrant to search for narcotics in her home. The deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as well as the deaths of other people of color killed by police in 2020, put a spotlight on racial injustice in the United States, igniting nationwide protests and catapulting the Black Lives Matter movement to the international stage at a time when the entire world was home watching.

Indeed, 2020 became a year that will not soon be forgotten not only because of a global pandemic, but also because of a worldwide reckoning calling on countries, communities, leaders, and individuals to confront and address irrefutable evidence that racial inequities continue to exist systemically and pervasively in our modern world in everything from housing to employment to education. In the United States, institutions of higher education responded by issuing calls to action to the members of their communities, forming committees, creating new positions, holding trainings and conferences, implementing new coursework, committing to diversity in hiring and admissions, holding vigils and townhalls, compiling resources, and recognizing “Juneteenth” as a university holiday for reflection. These institutional efforts are commendable and hopefully will facilitate progress towards racial equity in higher education, but true educational equity requires even more than programs, reflection, education, and sensitivity. It requires proactively seeking out solutions to disrupt the norms that keep disadvantaged populations disadvantaged within our spheres of influence.

For legal educators, one of our greatest spheres of influence is within the four walls of our classrooms, where we are charged with training students to become proficient attorneys prepared to engage competently and ethically in our twenty-first century world. But, in attempting to achieve these goals, many law professors still employ a 150-year-old teaching method as their primary teaching technique. This form of teaching, popularized by Harvard professor and Dean Christopher Langdell in 1870, combines a study of cases with the use of Socratic-method questioning. It is often referred to as the “case method” or “the Socratic method.” Though criticized and rejected by many legal educators at first, it eventually gained traction and became the accepted method of teaching at Harvard Law School and then the majority of other law schools in the United States by the early 1900s.

In the 100+ years since the widespread adoption of the Langdellian case method in legal education, the world has significantly changed as science, technology, and human evolution have shifted how people understand and interact with the world. Indeed, at the time Langdell introduced his method, the Wright brothers' first successful airplane flight would not occur for another 33 years, women would not have the Constitutional right to vote in the United States for 50 years, the United States Supreme Court would not find segregation of schools on the basis of race unconstitutional for another 84 years, and mankind was 100 years away from Neil Armstrong's first step on the moon. Moreover, Langdell and his colleagues likely could not even have imagined advances that would occur in the next 150 years in neuroscience and our ability to understand how the human brain acquires, understands, and retains new knowledge.

Despite massive advances in cognitive learning science, especially in recent decades, many legal educators continue to employ a teaching practice that contradicts scientific discoveries and instead choose to rely on a century-old teaching technique as their primary method for teaching. Professor Deborah Jones Merritt explains:

Legal scholars and lawyers know surprisingly little about the cognitive science research that has unveiled new methods of harnessing the brain to work harder and smarter. We are a profession that depends upon rigorous thinking, creative problem solving, and persuasive advocacy. Yet we have remained strangely oblivious to research about how the brain works.

To overcome systemic racism, each individual must inspect his or her personal sphere of influence not just to ferret out blatant racism, but to proactively counter systemic racism by looking for insidious threads of oppression. If legal educators do so, they will discover that the findings of cognitive learning science can no longer be ignored.

Simply put, the cognitive learning science of the last decade has demonstrated through countless empirical studies that best teaching practices, including the use of active learning, do not just increase the learning outcomes for all students; such practices increase learning outcomes for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, including students of color, disproportionately to the point where achievement gaps completely disappear. Additionally, the best teaching practice of active learning has many other positive effects on diverse populations, including increasing feelings of belonging, increasing self-efficacy, increasing course pass rates, and providing an environment of real educational equity where historically underrepresented populations speak and contribute at equal rates to their classmates. Finally, there is a plethora of scholarly research demonstrating that not only does the still widely-used Socratic method not rise to the level of active learning, but its continued use also hinders efforts within legal education to prepare students for legal practice and to create environments of educational equity where all students feel included, valued, and heard.

This Article asserts that one of the most critical steps to achieving educational equity in law school classrooms is replacing the Socratic method with active learning. Part II introduces and defines active learning, provides a brief history of its origin, gives several specific examples of it in practice, and explains why it is superior to passive learning. Part III explains why active learning results in greater equity in the classroom for underrepresented populations. Part IV responds to the first of two common misunderstandings about the use of active learning in law school classrooms-- that the Socratic method already is a form of active learning. Part V explains why the Socratic method hinders efforts within legal education to improve student preparation for legal practice and to provide educational equity within the classroom. Part VI responds to the second common misunderstanding about active learning--that it cannot be used to teach students higher forms of thinking, such as how to “think like a lawyer.” Part VII issues a call to action for law professors who are convinced by the arguments made in this Article.

Changing 150 years of the tradition and history of legal education, as well as individual professors' decades of teaching experience and teaching investment from carefully crafted lectures to entertaining unrealistic hypotheticals, will admittedly be an uphill battle for every brave educator who leaves behind comfortable pastures of familiarity and confidence to venture out into a 21st century world of learning, but never has it been so important. Superior learning gains for students is a worthy goal that will presumably incentivize many professors to seriously consider moving to an active learning teaching style, but working to create real equity in law school classrooms for all students should be a non-negotiable outcome for which every legal educator should strive.

[. . .]

Jean Jacques Rousseau said, “[T]rue education consists less in precept than in practice. We begin to learn when we begin to live; our education begins with ourselves ....”

We must, as educators, begin with ourselves. We must become invested, passionate, and committed to understanding and then applying best teaching practices as supported by cognitive learning science and the explosion of research from the past few decades in order to model and create an environment in which our students begin to learn by beginning to live themselves both in the classroom and out of the classroom as brilliant, capable, and engaged individuals who lead the learning as we guide them through the process. We can no longer be passive professors. The time has come for active learning to take center stage to improve the learning outcomes of all of our students and to build a bridge to greater educational equity for our underrepresented students.

Rosa Parks said, “To bring about change, you must not be afraid to take the first step. We will fail when we fail to try.” It is time for legal educators to take the first step.

Catherine Bramble is a professor of Legal Writing and Director of Academic Advisement & Development at the J. Reuben Clark Law School at BYU.

Rory Bahadur is the James R. Ahrens Chair of Tort Law at Washburn University School of Law.

Become a Patreon!